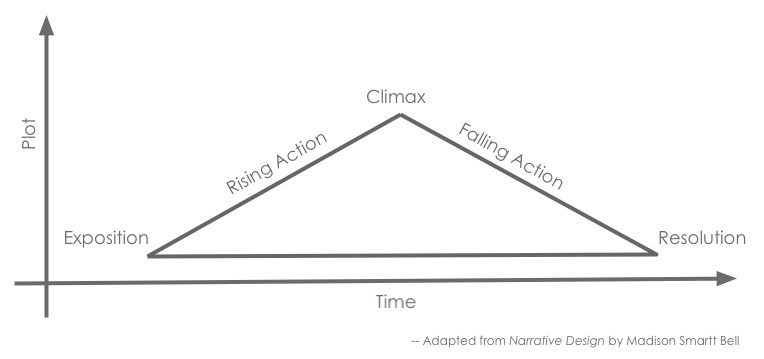

No, it’s not the title of Robert Ludlum’s latest thriller. But it is something you might remember from high school English. The Freitag triangle is perhaps the classic graphic representation of story progression (click on image for full size). Remember? “Every plot has to have a climax and a denouement.”

No, it’s not the title of Robert Ludlum’s latest thriller. But it is something you might remember from high school English. The Freitag triangle is perhaps the classic graphic representation of story progression (click on image for full size). Remember? “Every plot has to have a climax and a denouement.”

Did you know that you can apply the same structure to your nonfiction articles to make them as readable as — well, as readable as the latest Robert Ludlum thriller? Here’s how:

Find the conflict. In a traditional fiction story, conflict is what drives the plot. Characters cause stories to happen because they are trying to resolve some issue. The conflict is the energy expended in that effort.

In a nonfiction article, the conflict is somewhat different: you, the writer, are trying to get the reader to understand something important. The conflict is the tension exerted by the reader as they resist your persuasion. The climax of the article is the place you decide to put your best argument, your killer quote, or your unexpected twist. After that, the reader will concede your point.

If the reader still disagrees with you, at least it won’t be because you weren’t understood.

Provide the exposition. Ever see Austin Powers? Remember Basil Exposition? He comes along at the beginning of an adventure to tell Austin Powers what Dr. Evil just did and where he is now, so that Austin Powers can go fight him. That’s all exposition is: Michael York on a TV screen — or the writer’s particular variation thereof.

In a nonfiction article, this simply means that you should set the stage appropriately. Give the reader everything he needs up front to understand the situation as it stands now, before you begin to pull him along can you buy ventolin at asda through the story.

Build your story cumulatively. In fiction, each scene happens in such a way that the characters gradually acquire more information or experience to help them figure out what to do next. The more they know, the better choices they can make, moving the story to its climax.

In a nonfiction piece, you should lay out information for the reader in a logical, orderly way. If you’ve interviewed several people, present their quotes so that each one complements the one before it and segues into the one that follows. Let the evidence you’ve acquired tell the story for the reader.

Reveal the consequences. With the exception of John Sayles, storytellers don’t end their stories at the climactic moment. The denouement, or descending action, is the after-effect of the story’s climactic moment, when all the pieces of the character’s life begin to settle back down along a new axis. Readers want to understand the effects of the change on the characters they’ve come to care about throughout the story.

Likewise, once you’ve made your argument, you have to identify and explain the consequences to the reader. This is the so-called “takeaway message” of your piece.

Sebastian Junger, William Langewiesche, and Jon Krakauer are three of my favorite short-form nonfiction writers, and in large part it’s because they are master storytellers. Pick up an article by any one of them and you’ll read a paragon of narrative structure.

Writing a deadly boring article on farm subsidy reform? Interview someone who stands to lose something if the reform is passed. Interview someone who stands to gain something. Let their experiences dictate the story arc. And as you sit down to type, pretend — just for a moment — that you’re Robert Ludlum.